|

From Water To Ice:

How Ice Climbs Form

We are frequently asked questions about ice climbing conditions that are impossible to answer – and indicate a lack of understanding about how ice forms and what that has to do with climbing.

Anyone who claims to be able to predict ice climbing conditions has either not been around the stuff much or is not troubled by their predictions being wrong much of the time. When, where, and how much ice will form is impossible to predict (it is based upon the weather, which is equally unpredictable) but there are some factors governing the process that can help explain things – at least somewhat.

In glaciated areas, ice can form from snow under pressure (alpine ice) but in eastern North America, ice comes directly from water (water ice).

It takes just two ingredients to make water ice:

a water source and cold temperatures. The myriad possible combinations of these two ingredients is what makes ice formation so difficult to predict.

|

|

|

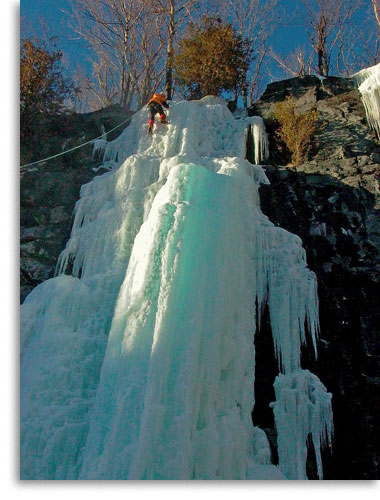

Well-formed ice

Photo by Mark Tierney

|

|

|

|

|

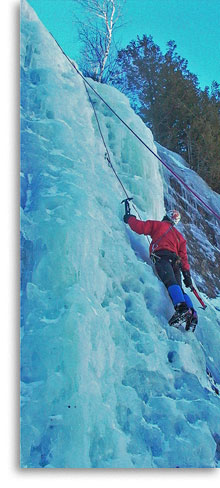

Never the same climb twice

Photo by Mark Tierney

|

|

Natural Water Sources

Ground water and intermittent surface water

This includes springs, seeps, and areas that collect runoff after rain or snow melt. Water from these sources generally flows slowly and not in great quantity, making it easy for the water to freeze and build up thicker ice. Most early season ice climbing is dependent upon this water source and many climbs can’t form at all without it. In years when summer and/or fall is rainy there is usually more water of this type available. Next time you get rained out of rock climbing, think of it as an investment in the ice season to come.

Streams, in the form of cascades or waterfalls

Although there is almost always water available, sometimes it is slow to freeze because the water flows too quickly or there is too much flow. Compared to other water sources, waterfalls generally require colder temperatures over a longer period of time to produce good ice. Once frozen, however, waterfalls frequently make for fabulous ice climbing. Barring warm temperatures, they also tend to build up quickly – often resulting in a “new” climb every day or so. Because water often continues to flow beneath the ice, extra caution is in order to avoid a mid-winter shower (or worse, a swim!).

Melted snow

When accumulated snow, on or above a climb, melts due to warm air temperatures or radiant heat from the sun, it can provide an ideal water source for ice formation. In some situations accumulated snow can also create an avalanche hazard.

Note: Pipes, hoses and spigots can be used to create artificial water sources – and great ice – but they hardly qualify as natural!

|

|

Cold Temperatures

How cold? How long?

If the temperature is cold enough, and there is ample water available, it doesn’t take long for ice to form. People are often surprised to learn that good ice can form, where there was none, in as little as 48 hours. A week is probably a more realistic period to allow in most cases. Warm (but not too warm) days and cold (but not too cold) nights generally make for the best ice formation. Daytime temperatures in the low 30’s F with nights below 20 F allow the ice to soften during the day and then refreeze and build up at night. Although very cold temperatures (below 0 F) will cause ice to form very quickly, the resulting ice is often brittle and shatters easily – not the best for climbing. Also, when it gets very cold the water source itself may freeze which suspends ice formation.

Never the same climb twice

Ice is constantly changing and it is this fact, along with the difficulty of predicting how it will change, that often gets rock climbers into trouble. Rock changes very little from day to day, season to season, and even over hundreds of years. Once in a while a holds breaks or something falls off but not often. Ice climbs usually change at least a bit each day and if you don’t expect and plan for it you will be surprised – sometimes unpleasantly. Often climbs change dramatically during a single day. On longer climbs, conditions sometimes change significantly while you climb. It is for this reason that we don't attempt to report conditions on a specific climb. More than once, we have arrived at the base of a route we have climbed on many previous occasions, only to find it in very different shape than we expected. The key to success lies not in being able to predict conditions but rather in knowing how to deal with the conditions you find.

|

|

|

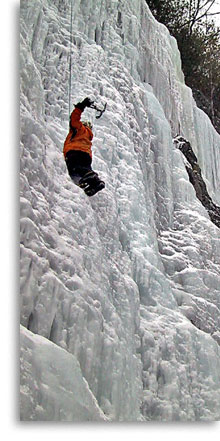

Cold, brittle ice

|

|

|

|

|

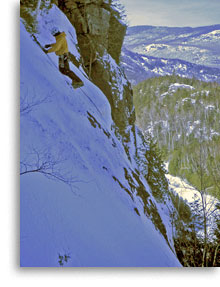

Climbing with a view

|

|

So how do I plan an ice climbing trip to the Adirondacks?

First, pick a time to visit. The most likely time to find good ice is from early January thru early March. This is also the most crowded time to visit – especially on classic routes. And rarely, the ice doesn’t cooperate at all and just plain disappears for a while. If you come earlier or later there is less chance the ice will be good and you may need to employ mixed climbing or winter rock climbing techniques – both can be a lot of fun or totally terrifying, depending upon how you approach them.

Second, and probably the most important advice we can offer non-guided climbers, is to have an idea of what climbs you might like to do before you come (a “Hit List”) but be sure to have lots of “extra” routes in case the one you choose is out of shape or full of climbers. Go take a look at it. Is it what you expected? Is it safe? This is exactly what we do.

In addition, keep in mind that you are the only one who can decide what’s reasonable and what’s safe enough for your risk tolerance. Even at its safest, ice climbing is still fairly dangerous. If you are not comfortable with a climb then don’t climb it! If you can't find anywhere else where you are comfortable climbing then don't climb at all. It’s far better to go bowling than get hurt on a climb you knew was not safe.

Finally, remember that even in very thin conditions, there is usually something interesting to climb, and a safe way to climb it – if you know where to look!

|

|

|

|

|

|